Please note: this post is 132 months old and The Cares Family is no longer operational. This post is shared for information only

Last week was the Public Wisdom 2015 symposium, curated by Cubitt Education. Income Development Coordinator Emily reflects on the afternoon.

“There's no such thing as an older person. There is only an older person in the community in which they live” – Anne Karpf

Last week, NLC’s Projects Officer Jess and I attended the Public Wisdom symposium: Ageing in Public. Along with dozens of other anthropologists, sociologists, artists and facilitators, we contributed to the discussion on whether our cities need to undergo a revolution for older people. It’s a debate worth having, and in my eyes, long overdue.

Despite the fact that people had travelled from right across the U.K to attend, conversation tended to centre on London. And rightly so; with it’s relentless pace and non-stop mentality, it can be a difficult city to navigate for the young, let alone the old. It’s cluttered streets and over-crowded public transport can sometimes leave one feeling the city is an unforgiving place in which to live.

Whilst many of us brave the pace – often with the aid of the latest app to get us from A to B – many do not, instead retreating inwards. Half of people over 65 face problems getting outdoors and instead stay behind closed doors in a “self-imposed house arrest” (a term coined by Chris Phillipson professor of sociology and social gerontology at the University of Manchester). Cities therefore become places for the young, with the older generation on the outskirts, barely visible on a day-to-day basis.

This isolation is a huge problem, and it only looks to get worse. By 2030, two-thirds of the world’s population will be living in cities, with a quarter of them over the age of 60. No longer can society ignore this issue.

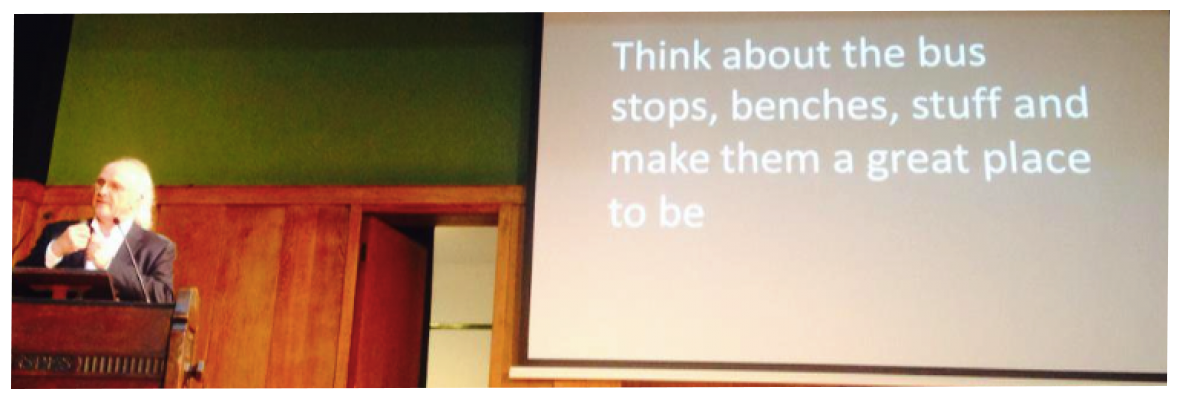

Ageing in Public offered a forum in which to examine how we can make our cities friendlier for the older generation. A lot of the debate focused on practical ideas, such as reconfiguring the geography of a city to make it more age-friendly. For instance, Nick Tyler, Chadwick Chair of Civil Engineering, UCL, suggested that we should make bus stops inviting places to visit so that the experience of travel becomes more pleasant. The issue of touch was discussed; whether our city is hard to touch and therefore, unattractive to negotiate. Dementia friendly cities were thought-on, alternative maps for different generations considered. There was certainly some worthy, blue-sky thinking. But for me, the most interesting conversation surrounded the concept of age.

Anne Karpf - who chaired the first discussion and kickstarted the debate with this article in The Guardian - questioned whether age is something we perform. Professor Richard Sennett, sociologist and author of The Fall of Public Man, suggested we need to re-think the idea of retirement, of stopping. Artist and performer Lois Weaver argued that society has created more of a divide between generations that there actually is. Throughout each of these shared opinions, I couldn’t help but feel proud of the work of North London Cares.

At every social club and for every Love Your Neighbour match, there is no such thing as ‘age’. There are just individuals, coming together, making friendships. Rude jokes are told, stories of heartbreak shared, the latest Hollywood blockbuster discussed. There is never a divide or a distinction. The connections made are invaluable and genuine. Everyone – both old and young - is visible, valued and appreciated. And there is no better feeling than that.

Ageing in Public certainly highlighted for me of the importance of the activities of North London Cares. It will take years, if not decades, to design age-friendly cities. But there is no need to wait for that revolution to break down generational divides. In fact, when you share a belly laugh with one of our older neighbours, you forget they even exist.